Python进阶笔记(三)

魔法方法

来看一个例子:

1

2

3

4

|

print(f"{1+2 = }")

print(f"{'a' + 'b' =}")

# 1+2 = 3

# 'a' + 'b' ='ab'

|

其实其内部发生了这件事:

1

2

|

print((x:=1).__add__(2))

print('a'.__add__('b'))

|

这种内置的方法也可以用于自定义的类中:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

|

from typing import List

class ShoppingCart:

def __init__(self, items: List[str]):

self.items = items

def __add__(self, another_cart):

new_cart = ShoppingCart(self.items + another_cart.items)

return new_cart

cart1 = ShoppingCart(["apple", "banana"])

cart2 = ShoppingCart(["orange", "pear"])

new_cart = cart1 + cart2

print(new_cart.items)

# ['apple', 'banana', 'orange', 'pear']

|

可以看到这里的+号是重载了运算符,使用了我们写的__add__方法,你一定会觉得类和类相加很奇怪,所以这就是为什么叫它魔法方法的原因了。

同样的,如果我们直接打印new_cart,得到的为类在内存中的地址,如果我们要重新定义打印出来的内容,便可以使用另外一种魔法方法,想要显示的内容完全可以自己定义:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

|

from typing import List

class ShoppingCart:

def __init__(self, items: List[str]):

self.items = items

def __add__(self, another_cart):

new_cart = ShoppingCart(self.items + another_cart.items)

return new_cart

def __str__(self):

return f"Cart({self.items})"

cart1 = ShoppingCart(["apple", "banana"])

cart2 = ShoppingCart(["orange", "pear"])

new_cart = cart1 + cart2

print(new_cart)

# Cart(['apple', 'banana', 'orange', 'pear'])

|

然后我需要打印类内items的长度,我也可以使用__len__魔法方法,最后将类可以像函数一样调用,则可以使用__call__方法:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

|

from typing import List

class ShoppingCart:

def __init__(self, items: List[str]):

self.items = items

def __add__(self, another_cart):

new_cart = ShoppingCart(self.items + another_cart.items)

return new_cart

def __str__(self):

return f"Cart({self.items})"

def __len__(self):

return len(self.items)

def __call__(self, *args):

for item in args:

self.items.append(item)

cart1 = ShoppingCart(["apple", "banana"])

cart2 = ShoppingCart(["orange", "pear"])

new_cart = cart1 + cart2

print(new_cart)

print(len(new_cart))

# Cart(['apple', 'banana', 'orange', 'pear'])

# 4

new_cart("x1", "x2")

print(new_cart)

print(len(new_cart))

# Cart(['apple', 'banana', 'orange', 'pear', 'x1', 'x2'])

# 6

|

学完了这些方法,可以使用一套题目来验证一下:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

|

class add:

pass

addTwo = add(2)

addTwo # 2

addTwo + 5 # 7

addTwo(3) # 5

addTwo(3)(5) # 10

# test:

add(1)(2) # 3

add(1)(2)(3) # 6

add(1)(2)(3)(4) # 10

add(1)(2)(3)(4)(5) # 15

|

快来完成这个类吧,答案放在下面:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

|

class add:

def __init__(self, num: int):

self.num = num

def __str__(self):

return str(self.num)

def __add__(self, other_num: int):

new_add = add(self.num + other_num)

return new_add

def __call__(self, other_num: int):

new_add = add(self.num + other_num)

return new_add

addTwo = add(2)

print(addTwo) # 2

print(addTwo + 5) # 7

print(addTwo(3)) # 5

print(addTwo(3)(5)) # 10

# test:

print(add(1)(2)) # 3

print(add(1)(2)(3)) # 6

print(add(1)(2)(3)(4)) # 10

print(add(1)(2)(3)(4)(5)) # 15

|

为什么不应该把列表直接作为函数的参数?

看一个简答的例子:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

|

from typing import List

def add_to(num, target: List = []) -> List:

print(id(target))

target.append(num)

return target

print(add_to(1))

print(add_to(2))

# 4304550208

# [1]

# 4304550208

# [1, 2]

|

你一定会很疑惑第二次调用的时候的结果,从target的id来看,它们是同一个。这是因为默认参数作为函数的属性,函数定义时就被定义了,而不是调用的时候才定义。

所以根据Pycharm内部的提示,我们不应该把这种可变的对象作为函数的参数。或者使用它作为参数时,函数中只取值而不对其进行修改,防止发生未预期的错误。

规范的写法如下:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

|

from typing import List, Optional

def add_to(num, target: Optional[List] = None) -> List:

if not target:

target = []

print(id(target))

target.append(num)

return target

print(add_to(1))

print(add_to(2))

|

从迭代器到生成器

Python中能够使用for循环迭代的对象叫可迭代对象,也叫iterables,包含__iter__方法。

我们可以通过hasattr来判断一个对象是否包含某个方法。

1

2

3

4

5

6

|

my_lst = [1, 2, 3]

my_int = 123

my_str = "123"

print(hasattr(my_lst, "__iter__")) # True

print(hasattr(my_int, "__iter__")) # False

print(hasattr(my_str, "__iter__")) # True

|

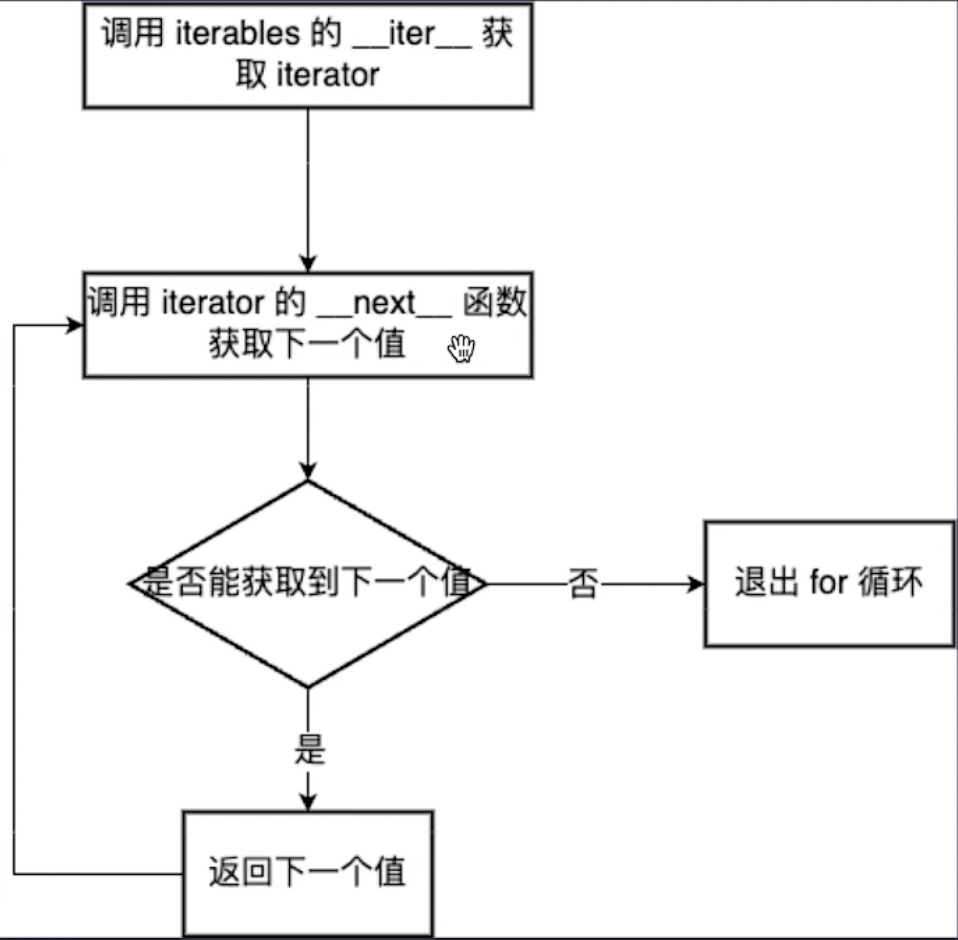

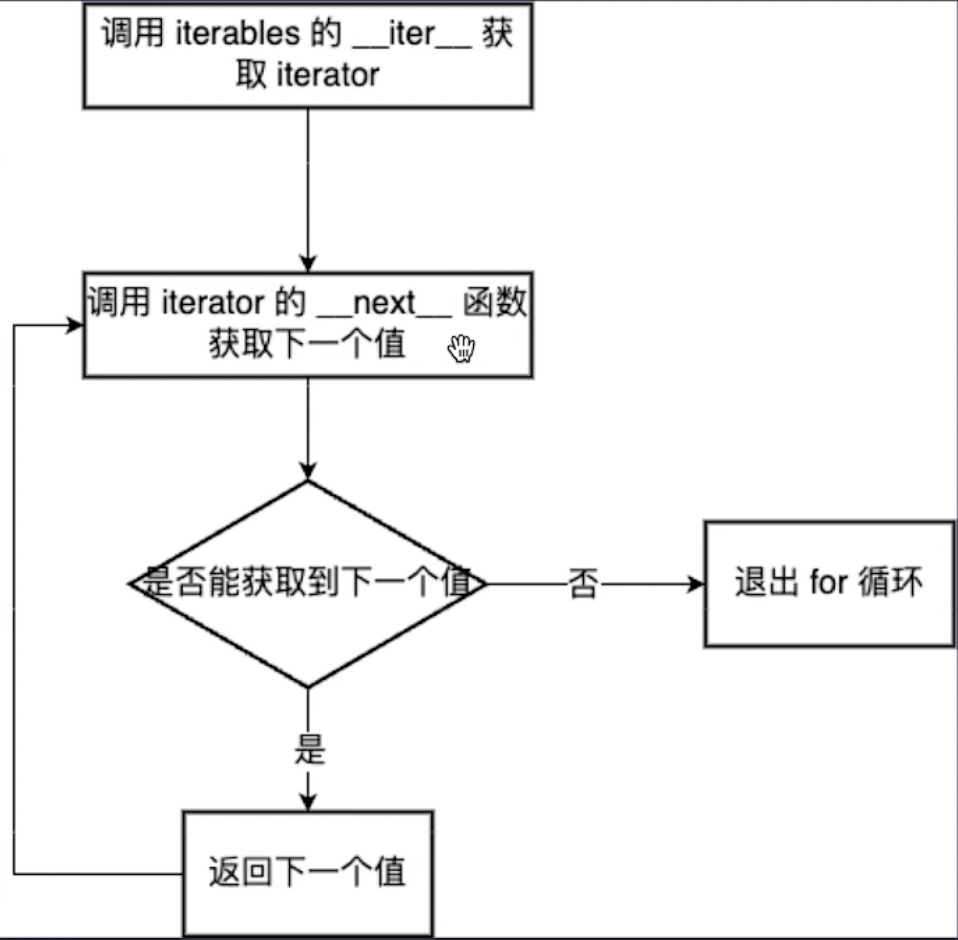

Python中的for循环底层发生的事:

使用while循环来实现上述过程:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

|

my_lst = [1, 2, 3]

it = iter(my_lst)

while True:

try:

print(next(it))

except StopIteration:

break

|

假设我们有一个日志文件,存储着结构化的数据,我们需要对其进行处理,通常的做法如下:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

|

import tracemalloc

def process_line(obj: str):

pass

file_path = "./logs/service.log"

tracemalloc.start()

with open(file_path, "r") as f:

lines = f.readlines()

for line in lines:

process_line(line)

current, peak = tracemalloc.get_traced_memory()

print(f"Current memory usage: {current / 1024**2} MB")

print(f"Peak memory usage: {peak / 1024**2} MB")

tracemalloc.stop()

# Current memory usage: 0.8936986923217773 MB

# Peak memory usage: 0.9117012023925781 MB

|

目前日志中的行数为5000行,假设日志文件为100w行,内存会直接达到200MB,而且这是处理函数为空的情况。

有什么更好的方法在处理大文件的读取处理呢?迭代器的方法就很适合。下面的例子通过一个自定义的迭代器来处理日志文件:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

|

import tracemalloc

def process_line(obj: str):

pass

filepath = "logs/service.log"

tracemalloc.start()

class LineIterator:

def __init__(self, file_path):

self.file = open(file_path, "r")

def __iter__(self):

return self

def __next__(self):

line = self.file.readline()

if line:

return line

else:

self.file.close()

raise StopIteration

line_iter = LineIterator(file_path=filepath)

for line in line_iter:

process_line(line)

current, peak = tracemalloc.get_traced_memory()

print(f"Current memory usage: {current / 1024**2} MB")

print(f"Peak memory usage: {peak / 1024**2} MB")

tracemalloc.stop()

# Current memory usage: 0.004233360290527344 MB

# Peak memory usage: 0.056969642639160156 MB

|

可以明显看到内存使用很小,且自定义的操作可以在__next__方法中实现。在自定义迭代器中,最重要的方法是__next__,__init__和__iter__显得很累赘。

Python中有另一种对象叫生成器,使用yeild关键字实现,它会自动产生__iter__和__next__方法。

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

|

def generator(n):

for i in range(n):

print("before yield")

yield i

print("after yield")

gen = generator(3)

print(next(gen))

print("---")

for i in gen:

print(i)

# before yield

# 0

# ---

# after yield

# before yield

# 1

# after yield

# before yield

# 2

# after yield

|

可以看到生成器是从哪里退出就从哪里进入的。

所以我们可以对自定义的迭代器类进行改造:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

|

def line_generator(filepath):

with open(filepath, "r") as f:

for line in f:

if line.split("|")[-1].strip() == "Create":

yield True

else:

continue

line_gen = line_generator(filepath=filepath)

for line in line_gen:

process_line(line)

|

使用上述生成器的写法和自定义迭代器的类写法是相同的,使用的内存都很小。

生成器的特点:

1.惰性计算,只有在迭代到这个元素时,才会生成它,而不是所有的内容先生成在读取,这样比较节省内存。

2.生成器可以没有终点。

给一道题写一下,提升理解:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

|

def multiplication_generator(x):

pass

gen = multiplication_generator(2)

print(next(gen)) # 1x2=2

print(next(gen)) # 2x2=4

print(next(gen)) # 3x2=6

print(next(gen)) # 4x2=8

|

答案如下:

1

2

3

4

5

|

def multiplication_generator(x):

index = 0

while True:

index += 1

yield f"{index} * {x} = {index * x}"

|

也可以用迭代器的写法:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

|

class Iterator:

def __init__(self, x):

self.i = 0

self.x = x

def __iter__(self):

return self

def __next__(self):

self.i += 1

return f"{self.i} * {self.x} = {self.i * self.x}"

|

Match Case

Python 3.10版本引入了match-case语句,它可以用来处理条件分支。

看一个交通灯的例子:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

|

def if_traffic_light(color: str) -> str:

if color == "red":

return "Stop"

elif color == "yellow":

return "Caution"

elif color == "green":

return "Go"

else:

return "Invalid color"

|

将它改写为match-case的版本:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

|

def match_traffic_light(color: str) -> str:

match color:

case "red":

return "Stop"

case "yellow":

return "Caution"

case "Green":

return "Go"

case _:

return "Invalid color"

|

虽然这看上去和C语言中的Switch Case很像,但是其支持的内容比c丰富的多。

- match case可以在匹配时进行解包和绑定变量:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

|

def if_point(point: tuple):

if len(point) == 2:

if point[0] == 0 and point[1] == 1:

print("Origin!")

else:

print(f"x={point[0]},y={point[1]}")

else:

print(f"{point} is not a valid point!")

|

改成match case版本如下:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

|

def match_point(point:tuple):

match point:

case (0, 0):

print("Origin!")

case (x, y):

print(f"{x=},{y=}")

case others:

print(f"{others} is not a valid point!")

|

这里的case(x, y)可以看出是进行了解包和变量绑定的,这里不使用_是因为其不能使用变量绑定,而others可以。

当然这里也可以灵活使用这个特性:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

|

def match_point(point:tuple):

match point:

case (0, 0):

print("Origin!")

case (x, 0):

print(f"On x-axis, {x=}")

case (0, y):

print(f"On y-axis, {y=}")

case (x,y):

print(f"{x=},{y=}")

case others:

print(f"{others} is not a valid point!")

|

在匹配序列的时候需要特别注意的是,默认其并不会匹配类型,而是直接解包,匹配内容:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

|

my_tp = (0, 0)

my_lst = [0, 0]

match my_tp:

case [0, 0]:

print("Matched tuple")

match my_lst:

case (0, 0):

print("Matched list")

match my_lst:

case 0, 0:

print("Matched list")

# Matched tuple

# Matched list

# Matched list

|

如果关心类型和值,或者只关心类型,则可使用如下方式:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

|

match my_tp:

case tuple([0, 0]):

print("Matched tuple")

match my_tp:

case tuple():

print("t is a tuple")

|

匹配完成之后,我们还可以进行一些其他操作:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

|

def match_quadrant(point):

match point:

case (x, y) if x > 0 and y > 0:

print("First quadrant")

case (x, y) if x < 0 < y:

print("Second quadrant")

case (x, y) if x < 0 and y < 0:

print("Third quadrant")

case (x, y) if y < 0 < x:

print("Fourth quadrant")

case (x, y):

print("On axis")

|

那么match case能否匹配字典和自定义的类呢?答案是可以。

看一个例子:

1

2

3

4

5

|

match dict_p:

case {"x": 0, "y": 0}:

print("Origin")

case {"x": x, "y": y}:

print(f"{x=}, {y=}")

|

如果只想匹配其中的某个关键字:

1

2

3

|

match dict_p:

case {"x": 20}:

print("Matched!")

|

同样的自定义类也是一样的:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

|

class Point:

def __init__(self, x, y):

self.x = x

self.y = y

p = Point(0, 1)

match p:

case Point(x=0, y=0):

print("Origin")

case Point(x=x, y=y):

print(f"{x=},{y=}")

# x=0,y=1

|

需要注意的是,类的定义可以使用位置参数,但是在case关键字使用时,类中必须使用关键字参数,否则会报错。

如果需要强行使用:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

|

class Point:

__match_args__ = ("x", "y")

def __init__(self, x, y):

self.x = x

self.y = y

p = Point(0, 1)

match p:

case Point(0, 0):

print("Origin")

case Point(x, y):

print(f"{x=},{y=}")

# x=0,y=1

|

最后修改于 2024-07-11

本作品采用

知识共享署名-非商业性使用-相同方式共享 4.0 国际许可协议进行许可。